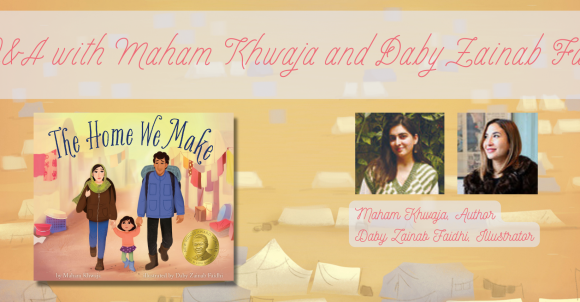

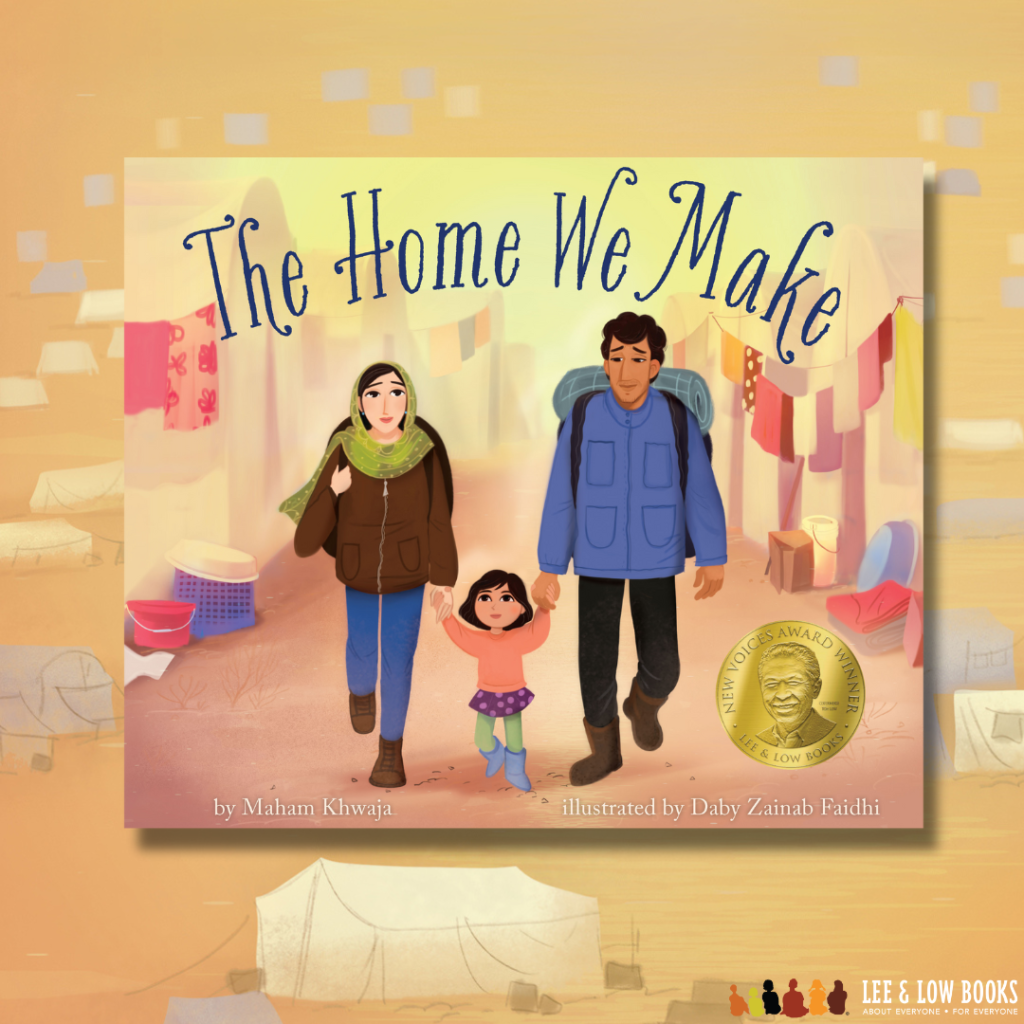

In this Q&A, author Maham Khwaja and illustrator Daby Zainab Faidhi share the backstory of their upcoming picture book and its many themes, including displacement, resilience, and the meaning of home. The Home We Make will be available on October 8, 2024!

Maham Khwaja is a Pakistani American writer and filmmaker. Maham has worked in feature film and network television production, as well as children’s programming, including Sim Sim Hamara (Pakistan’s Sesame Street). Currently, Maham is developing her first feature, Auntie Express, a story about a boisterous trio of Pakistani American aunties who run a successful food truck. The Home We Make marks her children’s book debut. You can learn more about her at mahamkhwaja.com.

Daby Zainab Faidhi is a versatile artist and illustrator acclaimed for her impactful work in animation, illustration, art direction, and painting. Her portfolio features contributions to award-winning film projects, including The Breadwinner, and most recently, co-art directing Merry Little Batman for WarnerBros. Explore her dynamic creations at zainabfaidhi.com.

The author’s note talks about your family’s displacement due to natural disasters, as well as your own immigration story. Can you share a bit more about what inspired you to write this book?

Maham: This story originated in response to the Muslim ban; the aftermath of which was heartbreaking. Once again, Muslims in the United States had to prove our humanity. Growing up as an immigrant kid from a country that, due to media misrepresentation, many people held misguided and racist views about Muslims, I was used to clarifying and deconstructing the narrative. After 9/11, I experienced those misguided views funneling into hatred and rage. Eventually, I stopped explaining. It was not my responsibility to calm the irrational fears of others. Instead, I continued educating myself and speaking my mind. Occasionally, I was told to go back to where I came from, and the pain from those moments is still palpable. No child should be made to feel that way, but it happened to so many of us. But we moved on best we could, grew up best we could, and tried to live best we could. And then the ban happened. The racism and Islamophobia had now barred people from entering this country based purely on where they were from. People in need of refuge and safety. People stuck in the crosshairs of other people’s wars, forced out of their beloved homes and communities. And the country I lived in, with its promises of freedom and goodwill, had slammed the door shut on them. I remember sitting down and writing this book with tears in my eyes, desperately trying to untangle the jumble of emotions I was feeling. To this day the refugee crisis barrels on with millions of people living in a state of constant destabilization.

This story, in particular, is a heavy one with a glimmer of hope. I knew I wanted to tell a hopeful story. In the refugee crisis the world has been facing, there have been many helpers, countless kind hearted souls who brought a bit of respite to the difficult journeys refugees have been forced to take. I wanted to show a realistic best case scenario. A scenario in which, yes, a family has to uproot and leave their homeland, but also a scenario in which they are treated with kindness and welcomed by others, and a scenario in which they are able to re-build and begin to heal.

What was your process for illustrating this book and why did you shape the illustrations in the way that you did?

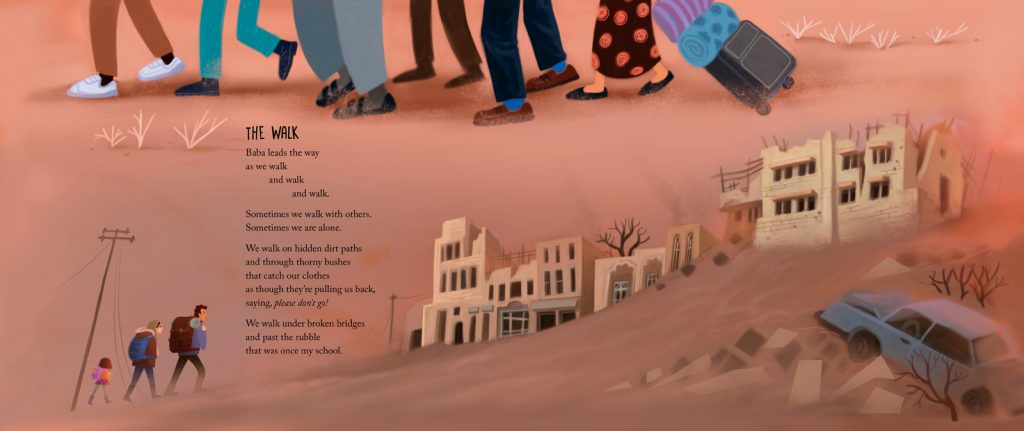

Daby: Illustrating this book involved using digital painting with Photoshop, along with gathering references, doing research, and watching immigration-related films for inspiration. I also created a visual library on Pinterest. I aimed for a realistic style, designing characters and environments that didn’t represent any specific culture but could be from the Middle East. I showed the characters to my editor and got feedback, then made a rough draft of the whole book. After approval, I digitally finished the illustrations, which took longer than expected. There were more changes back and forth until everyone was happy.

What research did you do to write this book?

Maham: I prepared by speaking with people from immigrant and refugee communities, some of them family and friends, and some of them people I’ve worked with as a teaching artist facilitating storytelling workshops. I also read countless news stories, watched films made by immigrants and refugees and of course, used quite a bit of my own memories and experiences as a young Muslim immigrant growing up in America.

What did you discover through the illustration process?

Daby: Throughout this process, I discovered that the book takes readers on an emotional journey through its chapters. To convey this, I played with colors and created moody environments to immerse readers in the same journey. Despite my full-time job, I had to work on weekends, breaks, or days off to finish the book. Keeping the style consistent over almost two years was challenging, especially when switching between projects with different styles.

Why did you choose to write this book in a poetry format?

Maham: Poetry is the way these particular words happened to flow out. I had images floating in my head that I began putting words to, that eventually, and very naturally became a story. The experience writing this book was quite different than my usual writing style which involves beat sheets, plot points, and character histories. For as long as I can remember, I have always kept a journal of poetry, but never thought of doing anything with it as writing poetry is predominantly a salve for whatever inner turmoil I may be feeling. However, this time, a story grew out of the turmoil, with characters that I knew and didn’t know at the same time, and it became an exploration of creating a home for them to live in, both figuratively and literally.

Your dedication is for “those who’ve left home, those who stayed, and those who have known the shelter of untroubled times.” Can you talk about your connection to the book and why you dedicated it this way?

Daby: I dedicated this book to “those who’ve left home, those who stayed, and those who have known the shelter of untroubled times” because I believe it’s a story that should reach people worldwide. It’s eye-opening for those who haven’t experienced such troubled times and comforting for those who have. I have relatives who went through similar experiences, and when my cousin told me about it, I imagined turning his story into art. A year later, when Lee and Low asked me to collaborate on this story, it felt like destiny.

What is “home” to you?

Maham: The summer we moved to America was full of firsts. Fried chicken for dinner. Dancing to “Can You Feel the Love Tonight” at the movie theater. Sleeping in bunk beds. Eating peanut butter. I remember the newness of everything. The foreignness.

But what I remember most about that summer is the water the day we went to the beach. The sand burned my feet but the water cooled them right away. When I stood still and looked out at the water, I felt like I was floating upwards and backwards at the same time. We stayed until dusk and I still didn’t want to leave. My father said, “We can’t stay here forever.” When I asked, “Why not?” My mother said, “Because we have to go home.” That’s the first time I heard it. Or at least, the first time I heard it and remembered it. Home. We were home.

One of the themes that runs throughout my writing is the search for the meaning of the word “home.” It is such a powerful word and one that haunts immigrants and refugees because something that is meant to provide stability, comfort, and a sense of identity becomes a very abstract, fluid idea when you move halfway across the world. What makes a place home? And what if home is not a place? Ultimately, for me, it’s a feeling of belonging. And it’s something many of us must learn to build, taking pieces from our lives, the moments of love and beauty and wonder, and fitting them together, however they happen to fit, into a home for ourselves.

Daby: My own family had to leave Iraq during the 2003 war and stayed in Jordan. It took me almost ten years to find the meaning of “home” in my heart and physically. “Home” for me is everywhere, a sanctuary where I can find peace, freedom, comfort, and security, surrounded by loved ones who support your growth and well-being.

What message would you like readers to take away from this book?

Maham: For those who have experienced or are experiencing the instability that comes from being separated from your beloved homes, I hope this book provides a sense of comfort and kinship. May you know the peace of home, in whatever shape it takes for you.

I’d like for readers to know that although this book is a work of fiction, there are millions of people facing the same issues the characters are, and just like the characters in the book, some are able to rebuild, while others unfortunately are not. I’d also like for readers to know that even though the family in this book chose to leave for their own safety, there are many people in these situations who choose to stay, or are unable to leave altogether. It is important to know that even though being put into the position to make such a choice is incredibly unfair, both choices are in turn incredibly courageous.

The family in the book was able to start rebuilding and met many people along the way, some who helped, and some who didn’t. Remember to be kind and welcoming because there are people who have had to weather many storms just to be where you are, safe and sound. You never know, you may just end up being a piece of someone’s puzzle, and they just might end up being a piece of yours. And you’ll both be one step closer to home.

Daby: I would like readers to take away a message of resilience, empathy, and the universal search for belonging from this book. Through the characters’ journeys, I hope to inspire introspection and compassion, helping readers appreciate the diverse experiences that shape our shared humanity.