**Spoiler alert**

I discuss the play in detail, so if you are planning on seeing Clybourne Park do not read this post.

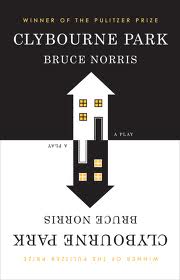

Ever since Clybourne Park won the Tony Award for Best Play for 2012 I placed it on my “must see” list. With Broadway neck deep in celebrity driven projects it is rare to see a play containing racial underpinnings win the top award. I avoided reading anything about the story beforehand, since I like to be surprised.

Here is a brief description from the play’s website: CLYBOURNE PARK explodes in two outrageous acts set 50 years apart. Act One takes place in 1959, as nervous community leaders anxiously try to stop the sale of a home to a black family. Act Two is set in the same house in the present day, as the now predominantly African-American neighborhood battles to hold its ground in the face of gentrification.

Since we frequently talk about race issues here on the blog, I was curious how these issues would play out in live theater. Race issues often make people uncomfortable, and the director and playwright made some interesting choices on how to tell this story in a dramatic setting.

Act One introduces Russ (Frank Wood), whose monosyllabic responses to his wife’s nervous banter make for good comedy, but later reveal underlying  problems in their marriage. When the local pastor, Father Jim (Brendan Griffin) and concerned neighbor, Karl (Jeremy Shamos) stop by the house the true gist of the story starts to simmer at first, builds to a boil, and ends with an all out blow out. Karl is concerned that Russ has sold his house to a black family, which in his mind could drag the neighborhood’s property values down and promote white flight. Russ seems to be surprised at this news at first, having been completely hands off with the realtor who sold his home, but warms to the news in an unanticipated way. The fact is, Russ sees this as an appropriate farewell to a community he secretly loathes. Russ feels his family was treated as pariahs because his only son committed suicide after returning from the Korean War under the suspicion of war crimes.

problems in their marriage. When the local pastor, Father Jim (Brendan Griffin) and concerned neighbor, Karl (Jeremy Shamos) stop by the house the true gist of the story starts to simmer at first, builds to a boil, and ends with an all out blow out. Karl is concerned that Russ has sold his house to a black family, which in his mind could drag the neighborhood’s property values down and promote white flight. Russ seems to be surprised at this news at first, having been completely hands off with the realtor who sold his home, but warms to the news in an unanticipated way. The fact is, Russ sees this as an appropriate farewell to a community he secretly loathes. Russ feels his family was treated as pariahs because his only son committed suicide after returning from the Korean War under the suspicion of war crimes.

The African American response is provided by Francine (Chrystal Dickerson), who works for Karl and his wife as a maid, and Francine’s husband, Albert (Damon Gumpton), who has the misfortune of picking his wife up from work as this neighborly dispute erupts. When an incredulous Karl asks Francine, hypothetically speaking, if money were not an issue, whether she would like to live in Clybourne Park, Francine can only say, “It is a very nice neighborhood,” since she doesn’t want to risk offending her employers with a response they may not like. Albert, on the other hand, is more forthcoming and speaks out loud the real question being asked of them, which is: “Would we want to live next door to white people?”

Russ’s wife Bev (Kristine Clark), whose world and marriage have just imploded for all to see, desperately turns to Francine as an ally, even going so far as to call Francine a friend while embracing the woman whose look of helpless discomfort speaks volumes. Bev wonders out loud why everyone—Black and White—can’t just live together. While Bev’s sentiments fall on deaf ears, the scene dissolves into a flashback of Bev’s son in military dress uniform as he writes his suicide note to his parents.

While Act One’s intentions were crystal clear, Act Two’s message is less so.

Scene from Act 2

Fifty years have passed and the same actors and actresses in Act One play equivalent characters. Clybourne Park has, as Karl predicted from the first act, become a predominately black enclave, whose real estate values are rising as the neighborhood is becoming desirable. Enter Lindsay (Annie Parisse) and Steve (Jeremy Shamos), a white couple who are buying the now decrepit house formally owned by Russ and Bev in the first act. Lindsay is pregnant and she and Steve plan to bulldoze the original house and start anew despite protests from the community to keep the historical integrity of the neighborhood intact.

Lena (Chrystal Dickerson) and Kevin (Damon Gumpton), an upper middle class black couple who holiday in Prague and Sweden, represent the community. Lena happens to be a direct descendant of Francine and knows the struggle and sacrifices previous generations made to buy homes in Clybourne Park. Lena is concerned about Lindsay and Steve’s plans for a new home and is worried about how it will change the neighborhood. “Because it only takes one house, and others will follow,” Lena observes. Steve, an educated white male, hones in on Lena’s choice of words and thinks he smells reverse racism. The audience audibly holds its collective breath as Steve plunges in and expresses his suspicions, which turns a cordial meeting of people talking about renovations and zoning laws into something for which they are completely unprepared.

Things get tense as Steve tries to get Lena and Kevin to admit that a racial subtext exists, while Lindsay, embarrassed, disavows any connection whatsoever to her husband. Lindsay also makes it known that she is a progressive liberal by interjecting things such as, “a lot of my friends are black” and “I once dated a black man.” None of these efforts by Lindsay does anything to calm the situation, nor keep everyone from almost coming to blows. At one point, both couples explore racial stereotypes by trading racist jokes to see if they can get each other to admit to being offended by the other. All parties leave angry and the play ends on an ambiguous note.

My one real problem with the play is that the white characters in both acts have more to say than the black characters. I could see this making sense in Act One because of the inequality between blacks and whites in 1959, but I do not see this making sense in Act Two. This racial imbalance concerning equal points of view did not sit right with me. For this reason, Clybourne Park did not draw me in emotionally. However, the play has grown on me intellectually as I have reflected on it. Also worth noting is that the racial mix of the audience was very diverse.

While Act One was about race and the fear of how integration would bring a neighborhood down, Act Two seemed to me to be about the perceived paranoia of race and how architectural choices could alter the aesthetic quality of a neighborhood. While fifty years is enough time for attitudes to shift regarding race, the interest in keeping real estate values high is a more enduring belief shared by black and white alike.

{Rating: 3.5 Stars out of 5}