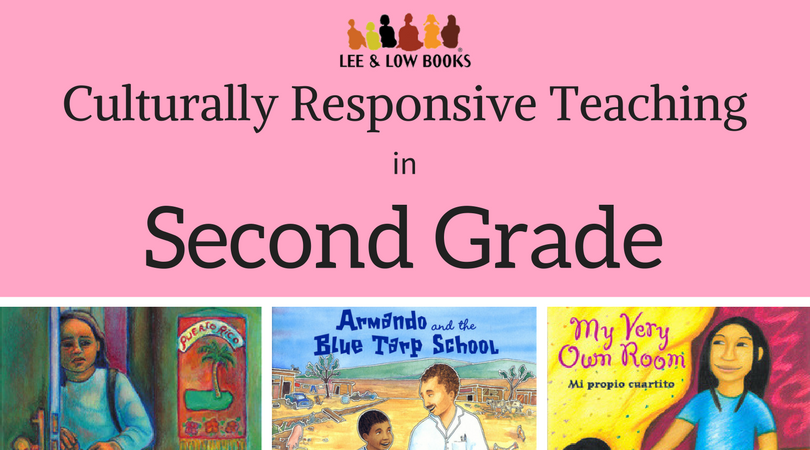

In this ongoing series, we explore what culturally responsive teaching looks like at different grade levels and offer concrete examples and resources. Last month we explored the intentional selection of texts for reading discussion in first grade. This month, educator Lindsay Barrett offers guidance on culturally responsive teaching in grade 2 by bridging between the familiar and unfamiliar in literature discussions.

More in this series:

- What is Culturally Responsive Teaching?

- Culturally Responsive Teaching in Kindergarten: Read Alouds to Build Relationships

- Culturally Responsive Teaching in Grade 1: Intentional Selection of Texts for Reading Discussion

- How Culturally Responsive is Your Classroom Library?

There is a key shift in Common Core’s expectations for students’ response to literature from first to second grade. In Grade 1, students “describe characters, settings, and major events.” In Grade 2, they move to describing, “how characters in a story respond to major events and challenges.” This is a tall order when you’re seven or eight, especially when you consider that a “major challenge” to someone this age could be anything from an argument with a friend at recess to a tragic event or significant family struggle. Whatever their experiences, many eight-year-olds’ worlds are still relatively self-focused. Empathizing with book characters that face unfamiliar challenges can be a reach.

We know that culturally responsive teaching hinges upon this perspective from author Lisa Delpit:

We must keep in mind that education, at its best, hones and develops the knowledge and skills each student already possesses, while at the same time adding new knowledge and skills to that base.

How can teachers support students by bridging familiar and unfamiliar book content?

Books with relatable characters who encounter multiple layers of events and challenges can provide familiar entry points while also stretching students’ thinking. Intentionally crafted discussions can help students make the leap from thinking about their own lives to thinking about the challenges others face. For example:

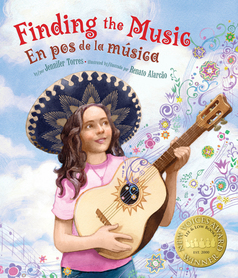

In Finding the Music/En Pos de la Musica, Reyna breaks a treasured instrument in a moment of anger and searches her neighborhood for a way to repair it. Many students will be able to relate to being frustrated with a family situation or wanting to fix a mistake, so these make helpful discussion openers. Questions like, “What does it mean to honor your family’s heritage?” or “What makes a neighborhood a community?” invite students into new thinking territory.

In Finding the Music/En Pos de la Musica, Reyna breaks a treasured instrument in a moment of anger and searches her neighborhood for a way to repair it. Many students will be able to relate to being frustrated with a family situation or wanting to fix a mistake, so these make helpful discussion openers. Questions like, “What does it mean to honor your family’s heritage?” or “What makes a neighborhood a community?” invite students into new thinking territory.

- The Have a Good Day Cafe tells what happens when other vendors encroach on the location of Mike’s family’s food cart. Many students will identify with Mike’s conversations with his grandmother, who yearns for the way things used to be in Korea and doesn’t always understand Mike’s modern preferences. Deeper conversations such as, “What’s the impact on an entire family when parents’ jobs are threatened?” and “How can honoring traditions be both challenging and beneficial?” could lead students to consider broader perspectives.

- Armando and the Blue Tarp School is the powerful account of a boy who is finally able to go to school when a teacher sets up a makeshift classroom at the Tijuana garbage dump where he lives. A discussion could begin with the universal question, “What makes a teacher great?” and progress to conversations about “Why is obtaining an education especially powerful for those who experience extreme hardship?” The “I wish my teacher knew” exercise publicized in connection with this book can be a way for teachers to learn more about the hidden challenges their students face that can inform their teaching in the future.

Culturally responsive teaching means viewing learning as a “socially mediated process,” so it’s not just important for students to read books that reflect their own challenges and expose them to those of others; they should also talk about these topics with peers. For example:

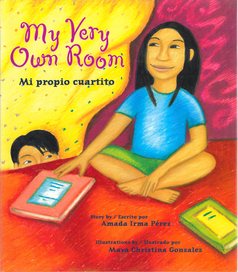

- Facilitate partner discussions of My Very Own Room/Mi Propio

Cuartito, which tells of a girl’s quest for some quiet space in a crowded house, and Soledad Sigh Sighs/Soledad Suspiros, the story of a girl who hates coming home each day to her empty apartment. Have partners discuss: “How does each main character respond to the challenges she faces?” “Who helps each girl and how?” “With which character do you identify more and why?” Hearing partners’ perspectives broadens students’ thinking.

Cuartito, which tells of a girl’s quest for some quiet space in a crowded house, and Soledad Sigh Sighs/Soledad Suspiros, the story of a girl who hates coming home each day to her empty apartment. Have partners discuss: “How does each main character respond to the challenges she faces?” “Who helps each girl and how?” “With which character do you identify more and why?” Hearing partners’ perspectives broadens students’ thinking. - After reading Tashi and the Tibetan Flower Cure, the story of a granddaughter who orchestrates a modern version of a traditional Tibetan practice to help her ailing grandfather, begin a partner discussion with the question, “What do you think about when someone you care for is sick or hurt?” Expand the conversation to, “How can connecting to others have healing powers?”

Talk to students about the power of literature to widen and deepen their worldviews. Using one’s own experiences to make sense of those of others is a powerful lesson for someone who is eight or eighty-eight.

About the Author: Lindsay Barrett is a former elementary teacher and literacy nonprofit director. She currently works as a literacy consultant and stays busy raising three young boys. Find out more about her work at lindsay-barrett.com.

About the Author: Lindsay Barrett is a former elementary teacher and literacy nonprofit director. She currently works as a literacy consultant and stays busy raising three young boys. Find out more about her work at lindsay-barrett.com.