In this guest post, Paul Bambrick-Santoyo and Stephen Chiger, co-authors of Love and Literacy: A Practical Guide for Grades 5-12 to Finding the Magic in Literature, share different ways that high school educators can approach text selection and build inclusive curricula.

Here’s a thought experiment: Consider the two high school book lists below. Which one would you prefer for a child you love?

All of the texts above are powerful, and all could make for fruitful study. But readers of this blog won’t likely need to be convinced of the advantages of list 2. A great curriculum makes space for more than one voice; it invites students to see themselves and each other through new eyes.

Why, then, do so many middle and high schools still look more like reading list 1?

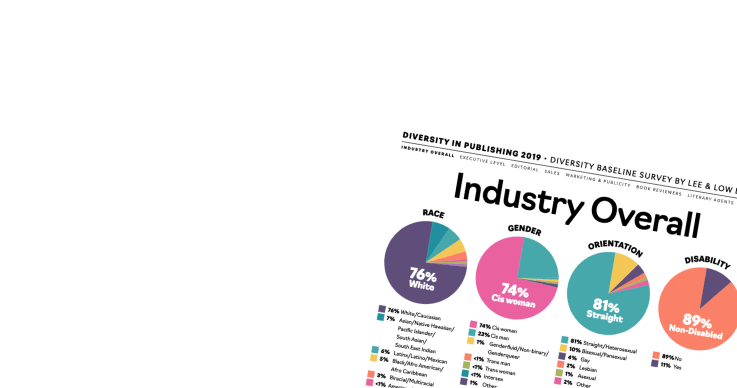

Change has come slowly to the upper grades for many reasons: budgetary challenges, institutional inertia, a teaching force (and generation of parents) who were raised on – and have understandable fondness for – texts like those on the left. In addition, college curricula presume certain sets of knowledge that middle and high school teachers feel obliged to include in their teaching. And undergirding it all is a publishing industry that has placed its fingers on the scale, preferencing white, cis-gendered, straight, and non-disabled authors and characters.

If you teach at – or know a child who attends – a school whose curriculum looks like Reading List 1, you can and should advocate for change. Encourage a collectivist approach to text selection that listens to voices across your community. Be an advocate for growth over time.

You are not, however, out of options to change the game right now, in the near term. Here are a few ways how:

You are not, however, out of options to change the game right now, in the near term. Here are a few ways how:

- Teach Counternarratives – As #DisruptTexts co-founder Tricia Ebarvia writes, reconsidering our curriculum doesn’t necessarily mean replacing all of our books. Instead, it often means complementing them with additional texts that give previously marginalized voices a place at the table. Teaching Othello? Spend time considering Desdemona and Emilia’s perspectives, even when the Bard doesn’t. Bring in Toni Morrison’s short play Desdemona, which centers these two characters, as well as Desdemona’s unseen and unheard Black nurse.

- Diversify your Library, whether it’s a classroom- or school-run operation – Whether or not your school provides time in the school day for independent reading, giving students access to texts for their own exploration and enjoyment is a powerful way to introduce choice to your class, develop a broad base of knowledge, and help your class build their own self-concept as readers.

- Classroom libraries: Rather than leveling your IR library, we recommend creating topic buckets/shelves where students can read increasingly complex texts on a single issue. Revamp and expand your collection to highlight traditionally marginalized voices and topics. Groups like Lee and Low publish lists to support you, such as their anti-racism books list.

- School libraries: Spearhead a review of the existing texts in the collection. Which voices dominate the conversation? Where could new voices be added? You can also adjust your displays and offerings to encourage conversations between texts, for example, pairing Kamel Daoud’s The Meursault Investigation with Albert Camus’ The Stranger.

- Embrace a Critical Lens – Even progressive texts are products of their times and their author’s world view. Scholar Gholdy Muhammad encourages us to consider, with each lesson, how what we teach helps our students understand the workings of power, equity, and anti-oppression. Let’s say you are reading To Kill a Mockingbird. In the text, Atticus Finch takes a largely gradualist approach to social change – waiting for it to happen bit by bit. It’s a privileged stance – one that feels cold, or even cruel, when viewed from the perspective of his Black neighbors. Imagine the class (or caregiver-child) conversation you could have around the question: Is Atticus’s position OK? Is he a hero or something else?

- Look Within – All of us are on a journey to be better versions of ourselves. Text selection gives us a unique opportunity to reflect on the books that shaped the way we see the world. Question your own possible biases and comfort zones. Challenge yourself to read a new perspective or amplify a voice that wasn’t prioritized in your own development. Around every turn is a fantastic find for your class – and yourself.

We shouldn’t have to wait for curricula to catch up to our world. But no matter what the situation at your or your child’s school, none of us is powerless. We can build the inclusive curriculum our children deserve right now. There’s no need to wait – and no time like the present.

Paul Bambrick-Santoyo and Stephen Chiger are co-authors of Love and Literacy: A Practical Guide for Grades 5-12 to Finding the Magic in Literature, available now. Steve blogs at stevechiger.com.