Last month we announced the six finalists for our 2015 New Visions Award. The Award recognizes a middle grade or young adult novel in the sci-fi, fantasy, or mystery genres by an unpublished author of color (our first New Visions Award winner, Ink and Ashes, will be released this June!).

As our award committee gets to know the finalists through their novels, we wanted to give our blog readers a chance to get to know these talented writers as well. We asked each finalist some questions. Here are answers from our first two finalists, Grace Rowe and Andrea Wang.

Below, authors Shilpa Kamat and Rishonda Anthony answer:

Shilpa Kamat, “Fallen Branches”

Shilpa Kamat, “Fallen Branches”

Tell us a little about the main character in your novel.

My novel is narrated by a teen named Shloka. Her voice jumped out at me one day when I was free writing during a spare moment in a parked car, and I knew she would have to keep talking until her story was told.

Shloka’s name means “song,” but she’s shy about singing. One of her mothers is of South Asian descent and the other traces her history to early immigrants who came to the town in Northern California where her family lives. When someone is killed in their seemingly peaceful neighborhood, Shloka finds herself working in secret with her friend Dilly to solve the mystery of what happened–something she’s sure is not quite what everyone else believes…

What advice would you give your younger self about writing?

Trust yourself and finish your projects. They don’t have to perfectly match your vision. In fact, they probably won’t. You don’t have to limit yourself to just one project at a time, but follow through. Take risks.

You’re already your harshest critic; learn to be an ally to your art as well. Choose to bring your writing to life rather than stifling it under the weight of your fears and expectations.

No matter how fantastical, ground your writing in real emotions and the interpersonal dynamics you witness or experience. Represent a broad range of people and centralize the communities and experiences you understand best. Be vulnerable. Let your characters have faults and forgive them, whether the other characters forgive them or not.

Rather than limiting yourself to the consciousness of current times, write with a sense of possibility. Take for granted that the seeds of positive social change will take root and come to fruition and write beyond that.

What is your writing process? What techniques do you use to get past writer’s block?

Although some aspects of my creative writing process are pre-meditated, I don’t always know what turn a story will take or what its characters will say.

This, to me, is what differentiates creative from analytical writing. Analytical writing is relentlessly driven by a point; creative writing is inspired and emergent. While a poem or a novel may be tempered by the frontal lobes, its source lies elsewhere. It may wind up dancing aside from an initial course and taking another. I see it as my job to respect this process and allow space for it while occasionally pruning or uprooting and replanting paragraphs.

To keep myself motivated while working on one major projects, I kept a daily log of my word count and tracked the amount written. With another project, I abandoned this method entirely, occasionally checking progress on the number of pages but no longer needing a sense of production to drive me. I have no tolerance for outlines, but I am comfortable artistically representing goals or documenting completed projects–drawing the petals of a flower to write in, for instance. To successfully keep myself organized, there need to be wild elements and vibrant colors.

As for writers’ block, in my experience, it manifests as either anxiety or forcing. Whether caused by an impending deadline or a desire to plow through a portion of writing so that I can build a bridge to another, forcing kills the dynamism necessary for artistic expression. If I recognize that I am forcing, I step outside or hum or dance or stand on my head–whatever it takes to make myself relaxed and present.

kills the dynamism necessary for artistic expression. If I recognize that I am forcing, I step outside or hum or dance or stand on my head–whatever it takes to make myself relaxed and present.

Similar approaches can help to alleviate anxiety, but when I am anxious, I may distract myself endlessly or find other chores to busy myself with. On my most difficult days, I can’t manage to write until I am so tired I’m ready to sleep. Then I relax enough to channel another chapter or two.

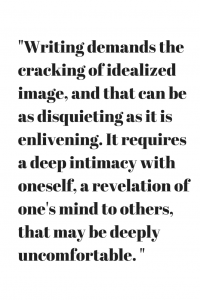

Writing demands the cracking of idealized image, and that can be as disquieting as it is enlivening. It requires a deep intimacy with oneself, a revelation of one’s mind to others, that may be deeply uncomfortable. The cure for my writers’ block is to sit with this discomfort and work my way into it, whether in a direct or roundabout way, until the truth emerges.

Recently, there’s been quite a lot of debate over the idea of readers who choose to take a break from books written by a certain group, such as white male authors. What’s your take on this?

When I was in middle school, my Social Studies teacher announced that we were predominantly studying white men because they were the ones who shaped the course of history. My Language Arts teacher vehemently declared that “man” can be used not merely to describe a man but all of humankind.

The teachers were preempting challenges to those conventions, but no one can out-shout the truth: people are hungry for narratives that have been repressed throughout history. During the past two decades, the social histories of slaves, women, low-income people, indigenous communities, immigrants, and others who were not part of the elite have been increasingly sought after and have even entered courses of study in some mainstream schools.

In college, I recognized that unless I was told otherwise, if I had to imagine a character in a book, I would imagine a white person. This flattening of imagination is detrimental to everyone; when mythical imagination is constrained to the worldviews of only a fragment of humanity, literature fails to realize its potential for developing empathy for a broad range of others and an awareness of human experience.

If there are people who choose to focus on works by a specific group of authors for a period of time, I imagine that they are struggling to broaden their imaginations to include, centralize, and normalize the experiences of those who are rarely represented. For instance, if people decide to read only foreign novels for a year, they may broaden an insular lens into a more global one. As long as no group is being permanently written off, no author permanently clumped into a single category, I see no harm.

What are your favorite books or writers in the same genre as your manuscript, and why?

When I was a young adult myself, I enjoyed Cynthia Voigt’s work; A Solitary Blue, for instance, explored painful family relationships while rooting the characters in the natural world. I also enjoyed a number of other novels, primarily in the science fiction and fantasy genre, but I have not revisited most of them as an adult.

As for the mystery genre, a novel I remember liking as a child was The Westing Game, and a novel I enjoyed as an adult was The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. The latter left me with a lovely image of someone’s sitting at the bottom of a dry well to think.

Tell us a little about the main character in your novel.

Cassandra Rose is a former child prodigy who won dozens of trivia contests, spelling bees, and brain bowls as a girl. After having a psychotic breakdown at the age of 12, she spent the next 5 years being home schooled in solitude. Now at 17, Cassandra is socially starved and desperate to fit in. But when she enrolls in a small private college, her past comes back to haunt her.

There are some autobiographical aspects in Cassandra’s character, which I believe is probably true for every author’s first book. In the case of Cassandra, I took them to the extreme. I was not a child prodigy who had a nervous breakdown, merely a gifted kid with anxiety issues. When I enrolled in a school rather similar to Cassandra’s college (in terms of size and atmosphere), I spent my entire first semester either alone in my room or going home on the weekend. This is where I formed the idea of a girl who is not an outcast due to social awkwardness, but because of a dark secret.

What advice would you give your younger self about writing?

First, don’t major in English. I’ve always loved books and have wanted to be a writer ever since I was a little girl (cliché, I know). But then I spent two college semesters analyzing deeper meanings and themes in genius level books. It gave me a complex, because I thought that if I couldn’t write anything as good as To Kill a Mockingbird or The Grapes of Wrath then there was no point in writing at all. Reading stopped being fun, and then writing became a chore rather than an escape. Even after I switched majors, it took a couple of years for me rediscover my love of writing.

Secondly, find a writing group! I’m the kind of writer who works well with a deadline, and when I’m writing a draft, my critique partners expect 10 pages a week, every week, from me. If I was writing for myself, I would procrastinate for years (see the third piece of advice). In addition, as part of the millennial generation, I crave instant gratification. Having someone review my work and give me feedback goes a long way towards motivating me to finish a project. All budding writers should check their local meetup.com and see if there is a writer’s group in their area. If not, consider creating one.

Third, keep at it! I started writing Seraphim when I was roughly Cassandra’s age. The story hasn’t changed much, but years of losing both faith and motivation quickly turned into more than a decade with nothing but a few vague chapters to show for it. I didn’t start seriously writing the story until I was in my late twenties, and only then when I found a writing group to support me.

What is your writing process? What techniques do you use to get past writer’s block?

I’m a huge fan of NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month). Both Seraphim and my latest novel started out as NaNoWriMo “Brain dumps” that got poured into a word document at a rate of about 2000 words a day. The 50,000 word result is always a mess, but at least it’s on paper. After that, I spend the next six months editing that work into a proper draft.

The best technique to get past writers block is to stop reading. I’m a big reader (I know the location of every library in my city and have subscriptions with Audible, Amazon Prime, and Forgotten Books) and I believe that no one can be a serious writer unless they are also a serious reader. But when I can’t write, usually it’s because the books (yes, plural) I’m reading are hurting the process. For example, the author’s style might rub off on me, and I’ll unknowingly change a character or my voice. Then I’ll start to struggle, because the book doesn’t sound quite right, and I’m not sure why. Or I might come across an idea that I really like, and then decide to put something similar in my book. Suddenly I’m trying to add an alien into a book about witchcraft, or trying to create an entire fantasy realm for a story that really doesn’t need it. That’s a recipe for instant writer’s block. Forcing myself to step away from other people’s work and focus on my own (usually for no more than a week or two) gets me out of most ruts.

Recently, there’s been quite a lot of debate over the idea of readers who choose to take a break from books written by a certain group, such as white male authors. What’s your take on this?

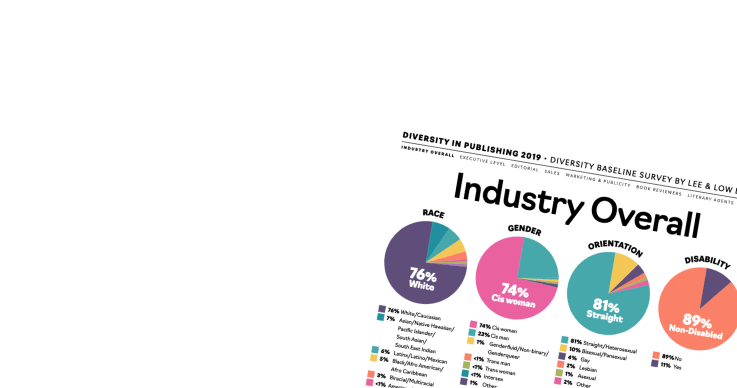

In doing research to answer this question, actually had to face the uncomfortable fact that that there are very few authors of color sitting on my bookshelf (as you will see in the next question). This was not intentional, as I  certainly want to read more diverse authors, but considering that publishing is still a very white business (white authors are more likely to get published and more likely to get coverage for their books), these stories don’t just fall into my lap.

certainly want to read more diverse authors, but considering that publishing is still a very white business (white authors are more likely to get published and more likely to get coverage for their books), these stories don’t just fall into my lap.

However, I do believe in the power of the free market, and I think that if more people buy books by diverse authors, publishers will start putting out more books by diverse authors. For me, it involves deliberately seeking out books written by authors of color and including those books in my usual reading rotation. Despite this, I don’t think I would go so far as to cut out all white male authors. Ninety percent of the books are read are adult Urban Fantasy, Epic Fantasy, and Horror and there aren’t many authors of color who write in those genres. But one day, I’d like to count my name among those authors.

What are your favorite books or writers in the same genre as your manuscript, and why?

In Young Adult, I’m a fan of Susan’s Ee’s Penryn & the End of Days series and The Mortal Instruments by Cassandra Clare. As for fantasy, I love Jim Butcher’s The Dresden Files and George R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones. When it comes to the pinch of horror I like to put in every story, I have to recognize Joe Hill, and his father Stephen King, who I grew up reading and who wrote the first 1000 plus page book I ever read (It, age 15).