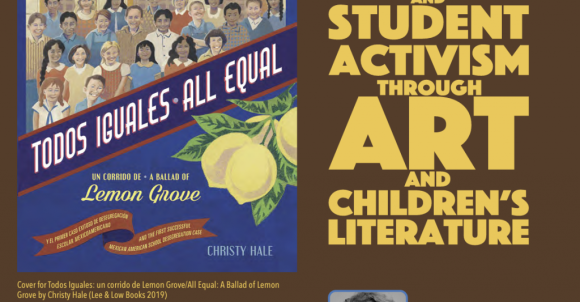

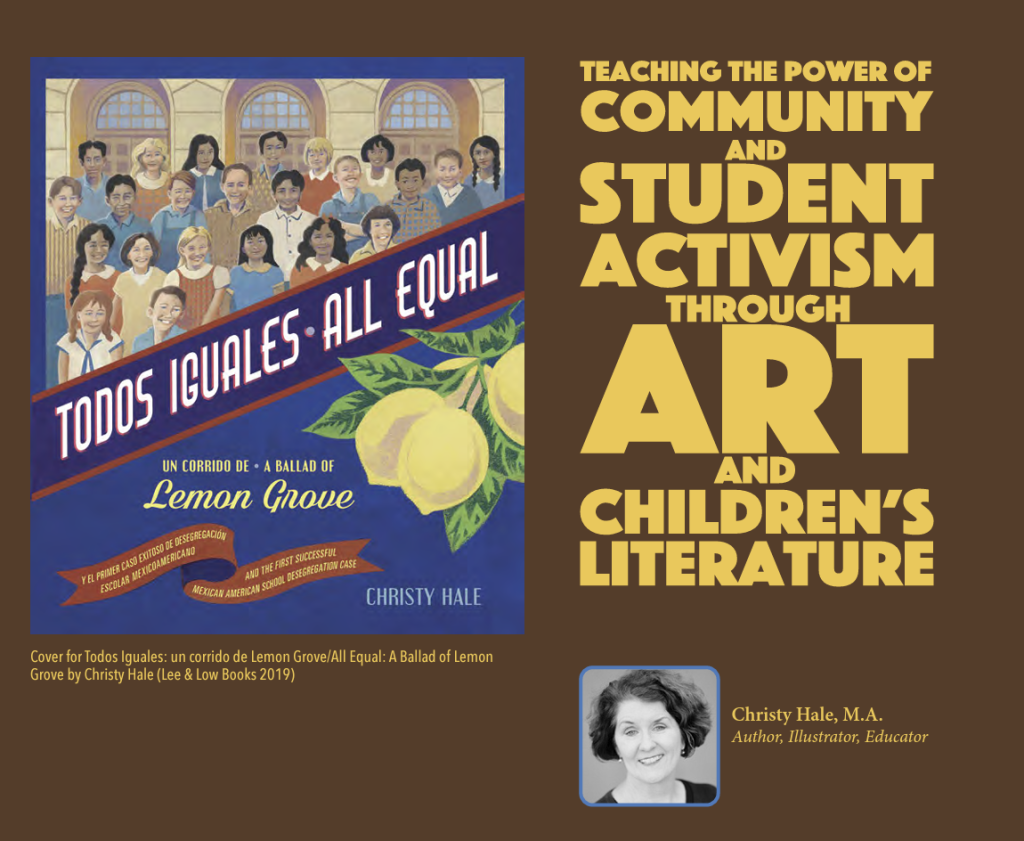

This essay by author Christy Hale originally appeared in the CABE 2023 Edition of Multilingual Educator. Christy is the author of Todos Iguales: Un corrido de Lemon Grove/All Equal: A Ballad of Lemon Grove. Her latest book, Copycat: Nature-Inspired Design Around the World, is available now!

Christy Hale has illustrated numerous award-winning books for children, including Dreaming Up: A Celebration of Building and several other titles for Lee & Low Books. As an educator, Hale currently teaches picture book writing at the Academy of Art University in San Francisco. She has also taught art and graphic design to high school students, and first learned about the Lemon Grove case at an in-service teacher workshop. Hale and her husband live in Palo Alto, California. You can visit her online at christyhale.com.

Do you want your students to feel hopeful, connected, and engaged? To become thinkers, problem-solvers, and doers? Protesters have come in all races, classes, genders, nationalities, and ages. The common unifier is a dedication to justice.

Children’s literature can be a critical, moving medium to showcase (current and historical) activism and inspire our students through voice and action.

Canto por la esperanza,

del pueblo en comunidad,

los héroes de Lemon Grove

lucharon por la igualdad.

I sing to you of hope,

the power of community,

and the heroes of Lemon Grove,

who fought for equality.

This corrido is from my book TODOS IGUALES: Un corrido de Lemon Grove/ALL EQUAL: A Ballad of Lemon Grove. It is based on a true story of the 1931 Lemon Grove Case, Roberto Álvarez v. the Board of Trustees of the Lemon Grove School District. This was sixteen years before the Méndez v. Westminster case that ruled that separate schools for children of Mexican descent were unconstitutional and twenty-three years before Brown v. Board of Education declared that school desegregation was unconstitutional throughout the country.

In 2012-2013, I taught art and graphic design at a high school in the Bay Area. During an in-service workshop, I learned about a historic Lemon Grove case that occurred in San Diego County. Why had I never heard of this before? I went home that night and started doing further research.

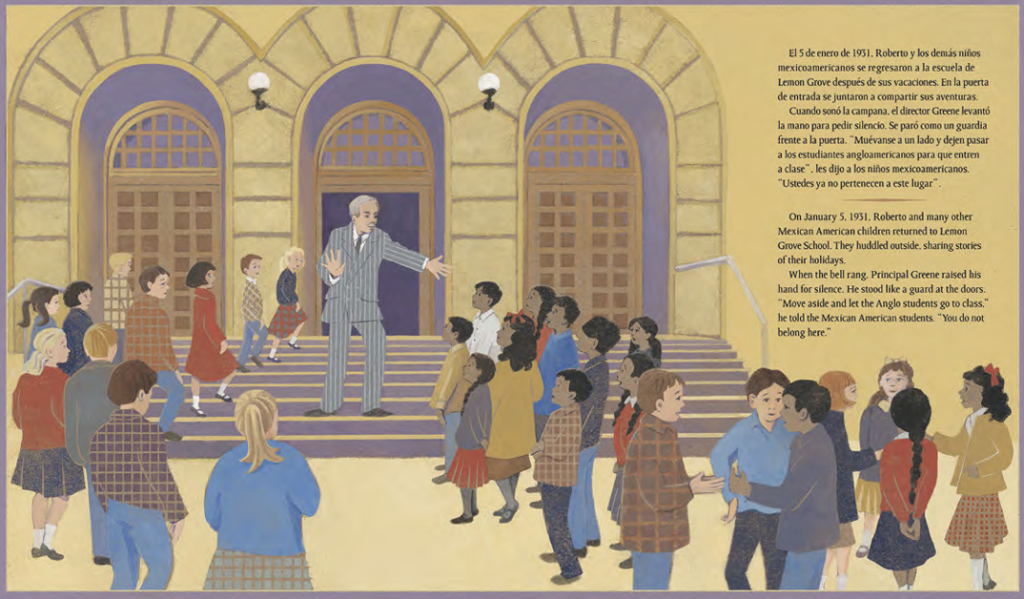

To summarize: In the summer of 1930, the Mexican families of Lemon Grove learned of a plan to segregate their children in a small, inferior school. On January 5, 1931, the principal blocked the Mexican American students from entering the school and directed them to go to the new inferior school.1

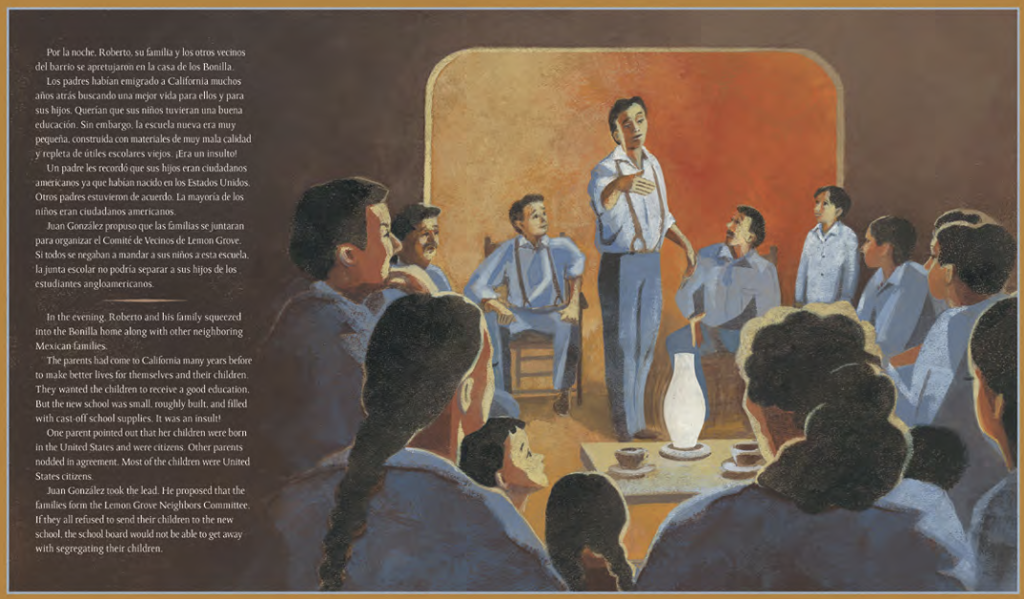

The Mexican parents were outraged. They organized a community activist group. The children boycotted the school. The parents filed a lawsuit against the school board, with twelve-year-old Roberto Álvarez as the plaintiff.2

In exploring how I wanted to share this story with students, I thought about what visual and written form would appeal to young readers while honoring the community and time period.

My sources included consulting materials from Robert R. Álvarez Junior, the plaintiff’s son. His book, Familia, described the strong family and friendship connections in the Lemon Grove Mexican community, many of which had begun decades before in Baja California. Some fifty families from Baja California settled in the San Diego area, creating a supportive and stable community.3 I believe this was a key factor in the ultimate victory.

The Lemon Grove Historical Society and the Lemon Grove Oral History Project were further instrumental in introducing me to the families involved in the Lemon Grove Incident.4 Often lost in studying the progress or lack of progress in civil rights and school desegregation are the community and individual family voices instrumental to change. I was moved to create a story about Lemon Grove that centers around young people taking a stand and the parents calling out the inferior education on offer. The new school was poorly constructed, and the books and supplies were all second-hand castoffs. The families had come to this country to make better lives for themselves and their children.

The Lemon Grove School Board naively or dismissively assumed that the Mexican American community would go along with or accept their decision. They never solicited the community’s opinion. The school board underestimated the strength and interconnectedness of this community. When Juan Gonzáles organized the families, their collective voice was powerful.

Help prepare our students to be active, informed members of society by conveying that their thoughts and opinions matter. Give them opportunities to share constructively with those around them. Allowing students to speak and have their words heard, respected, and validated helps them to figure out their beliefs and embrace their identities. Also, give opportunities to work collaboratively and find their collective voice.

Activism helps develop communication, connections, relationship building, and critical thinking skills and makes meaningful contributions to society.

Ideas for teaching about community and youth activism with students:

- Work with your public or school librarian to build a collection of books that span communities working towards social justice across races, classes, genders, nationalities, languages, ages, and time periods.

- Reach out to your local historical society to learn about your city, town, or neighborhood’s historical activism. What mattered to earlier generations, and are those still issues in the community today?

- Have your students interview an adult mentor about their experiences fighting for something they believe in or going through hardship. How did the person react to and handle the situation when they faced obstacles? What does the person remember about the political climate during their youth? What advice does the person have for someone trying to take up a cause and stand up for justice today?

- Have your class research other young activists of today. Divide into groups and answer these questions: What are their causes? What did they accomplish, and what does their current work look like? How did they raise awareness regarding the causes about which they were passionate?

- Conduct a “Social Change” project in your classroom. Brainstorm a list of different causes for which students would want to fight. Pick three. In groups, research the topic and come up with a way to enact change: a letter, a flyer, a petition, an online campaign, a song, and so on.

- Have students research school desegregation today and its impact on modern society. How is school desegregation still evident in major cities? How are families and students fighting against school desegregation? What is needed to advocate against school desegregation?

- Conduct a research project about the importance of music and song during social justice movements. How and why are music and song important during difficult times, and how do they play a role in uniting people?

- Examine both contemporary and historic social protest songs. One article I read discusses how “Hip-Hop Continues a Protest Tradition That Dates Back to the Blues”: https:// www.yesmagazine.org/social-justice/2020/08/07/music-blmmovement.

The author’s notes, bio, and list of publications are included in the appendix of the online version: https://tinyurl.com/2023onlineME.