![]()

Marilisa Jimenez-Garcia, research associate at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Hunter College, CUNY, graduated from the University of Florida with a PhD in English, specializing in American literature/studies, nationalism, and children’s and young adult literature. Marilisa is also a National Council for Teachers of English (NCTE) Cultivating New Voices Among Scholar of Color Fellow. She is currently working on a manuscript on U.S. Empire, Puerto Rico, and American children’s culture. She is the recipient of the Puerto Rican Studies Association Dissertation Award 2012 and the University of Florida’s Dolores Auzenne Dissertation Award. Her scholarly work appears in publications such as Changing English: Studies in Culture and Education and CENTRO Journal. She has also published reviews in International Research in Children’s Literature and Latino Studies.

Marilisa Jimenez-Garcia, research associate at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Hunter College, CUNY, graduated from the University of Florida with a PhD in English, specializing in American literature/studies, nationalism, and children’s and young adult literature. Marilisa is also a National Council for Teachers of English (NCTE) Cultivating New Voices Among Scholar of Color Fellow. She is currently working on a manuscript on U.S. Empire, Puerto Rico, and American children’s culture. She is the recipient of the Puerto Rican Studies Association Dissertation Award 2012 and the University of Florida’s Dolores Auzenne Dissertation Award. Her scholarly work appears in publications such as Changing English: Studies in Culture and Education and CENTRO Journal. She has also published reviews in International Research in Children’s Literature and Latino Studies.

How might the legacy of the first Latina librarian at the New York Public Library speak to recent ‘human events’? 2014 was a landmark year with regard to discussions of race, diversity, and young people of color in American society. A game-changing year in which much of the rhetoric of multiculturalism we often use when preparing our young citizens unraveled. Indeed, by summer 2014, events had sparked a campaign by educators looking for new approaches and resources on how to discuss race in the classroom (Marcia Chatelain, “Ferguson Syllabus”). Those of us focused on the narrative and social literacy of young people seem at a place of no return—a place where we must admit that equality is not so in the Promised Land.(1)

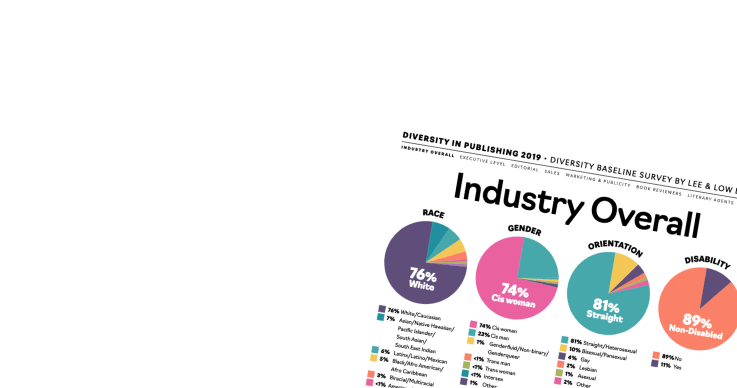

As an American literature and childhood studies researcher, I was not surprised that 2014’s list of recurring headlines, including court rulings, protests, and policing, also contained debates about children’s books. What young people read, and the worlds, norms, histories, and people therein, have always mattered in the U.S. Children’s reading materials (e.g. fiction, history, and textbooks) have always been at the forefront of the “culture wars,” particularly after the Cold War. Ethical pleas for kid lit diversity are also nothing new. The start of Pura Belpré’s NYPL career in the 1920s is actually marked by a question similar to Walter Dean Myer’s op-ed in New York Times: “Where are the people of color in children’s books?” In Belpré’s case, she wanted to represent what she saw as the history and heritage of the Puerto Rican child. She began writing her own books as result of finding Puerto Rican culture absent from the shelves. However, considering the contributions by people of color to children’s literature over the last 90 years or so including Belpré, and numerous studies on the lack of representation, we find that calls for kid lit diversity consistently fail. (For further information see Nancy Larrick’s study “The All White World of Children’s Literature” The Saturday Review, September 11, 1965 and also work by the Council for Interracial Children’s Books). Post-2014, what is remarkable about our current moment is the amount of mainstream and field-wide attention the diversity issue has garnered. It also remains to be seen how the incorporation of We Need Diverse Books will impact the literary world.

Here, I want to offer some reflections on Belpré’s career and legacy which might enable us to have a more critical, productive conversation on diversity:

Here, I want to offer some reflections on Belpré’s career and legacy which might enable us to have a more critical, productive conversation on diversity:

Conversation instead of compartmentalization. People of color including librarians and storytellers such as Pura Belpré and Augusta Baker were active (1920s and 1930s) when American children’s literature was advancing as a field with its own set of publishers, librarians, and prizes. The African American and Puerto Rican community have a longstanding tradition of employing children’s literature as a vehicle for imagination, cultural pride, and social consciousness.(2) Yet, systemically, people of color are left out of the conversation when it comes to accessing the breadth of children’s literature as an American tradition. Diversity should be understood as a conversation, rather than as a system of containing U.S. populations as compartments (with respective histories, literature, and cultural iconography) that never converge. A compartmentalized view hinders our ability to envision people of color as participants in the imagined landscapes of American history and culture—past, present, and future. Even our prizing system, including the Belpré Medal, tends to follow this logic of best Latino children’s literature, best African American children’s literature, but when it comes to best American children’s literature, people of color have historically fared in the single digits. Prizes such as the Belpré foster cultural pride, solidarity, and a market for Latino authors, yet they also continue the logic of compartmentalization.

Relevant instead of relatable. Belpré’s stories were based on folklore which some Latino/a children might find familiar. But, Belpré’s books are also artistic fiction. In other words, they are just stories to be enjoyed by whoever might enjoy them. As a teacher, I had to check my use of the term “relatable” when discussing literature with young people. Once we were reading The Outsiders (1967) and Nicholasa Mohr’s Nilda (1973) as means of comparing how young people grow up and encounter violence. I always remember one student closing her copy of Nilda, saying, “This is about culture, not about teens. I couldn’t really relate.” I was puzzled seeing that key characters in both books were adolescents. Certainly, when a Latino/a author writes about Latino/a characters, the story is shaped by Latino/a culture—which also varies in terms of racial, regional, gender, and national identity. But, the same is true for any author. Oliver Twist is a mainstream story, but it is also a commentary on 19th century childhood—a celebrated time for some who could afford it—and the conditions for poor, orphaned youth. Stories are always about culture. Yet, what we catalogue as “foreign” or “other” tells us more about ourselves than about the stories we read.

Imperfect characters instead of superheroes. When it comes to young readers, we have a tendency to want to simplify things that we adults even have a hard time understanding. Clearly, cognition is an issue. But our desire to create clear-cut heroes and villains in American history, or any history for that matter, will fail at best. Parents and teachers often battle for the representation of marginalized groups in textbooks. But, they rarely argue over whether or not America is an exceptional nation (Zimmerman).(3) Our approach to teaching and systemizing a heritage of American children’s literature should emphasize that this is a great nation shaped by imperfect people, whether dominant or marginalized. It’s complicated. Those we might see as heroes don’t always win or dominate “the bad guys.” In Belpré’s folklore, she often underlined this sense of imperfection. For example, she showed that even though the Tainos had beautiful values and bravery, they didn’t win every battle against the Spaniards (Once in Puerto Rico, 1977). Even the Medal named in her honor symbolizes this sense of complicated, converging histories in its use of the term “Latino/a.” This one term—which some even within our communities cannot agree upon—stands for those who represent multiple nations, histories, languages, and races. It’s not a perfect term. Nor, as my father always tells me, is this a perfect world. Sooner or later, our young people are going to learn that apart from any storybook or textbook. The pressure to present a perfect America often means that we erase the voices of the marginalized.

Here are some practical ways these principles might play out in the classroom:

- Consider talking with students about diversity and how they “see themselves” in books: Even with the best intentions, we have a tendency to talk about young people without asking their opinions. Try to have it start with them. If they are a bit older, have them read Walter Dean Myers op-ed for class discussion. You might ask them to journal about issues such as cultural authenticity in a book read for the class. Or you might ask them to write a story, graphic novel, science fiction adventure, or picture book about their communities as an assignment.

- Consider classroom presentation of books: We need to stop relegating people of color to special months in which we celebrate and include their stories. Although focusing on a particular group has its benefits, this should not override the other 11-months when they are excluded or barely mentioned. This also includes displays of books in your class library. Do you organize books alphabetically by author or by nationality and country?

- Consider genre: Avoid relying only on folklore, historical fiction, and biographies. This is also something publishers need to consider. Latino/as in particular have one of the lowest percentages in fantasy, science, and science fiction. Look for books in which people of color play active roles in actual and imagined societies.

For further reading:

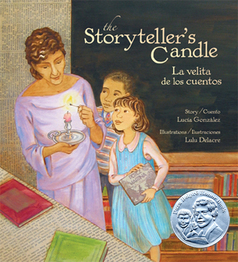

Pura Belpré Lights the Storyteller’s Candle: Reframing the Legacy of a Legend and What it Means for the Fields of Latino/a Studies and Children’s Literature by Marilisa Jiménez-García in CENTRO Journal.

- R.L. L’Heureux, Inequality in the Promised Land (Stanford University Press, 2014)

- Katherine Capshaw-Smith, Children’s Literature of the Harlem Renaissance (Indiana University Press, 2006) and Marilisa Jimenez-Garcia, “Pura Belpré Lights the Storyteller’s Candle” (CENTRO Journal, Vol. 26, No. 1)

- Jonathan Zimmerman, Whose America?: Culture Wars in the Public Schools (Harvard University Press, 2002)