![]() Jaclyn DeForge, our Resident Literacy Expert, began her career teaching first and second grade in the South Bronx, and went on to become a literacy coach and earn her Masters of Science in Teaching. In her column she offers teaching and literacy tips for educators.

Jaclyn DeForge, our Resident Literacy Expert, began her career teaching first and second grade in the South Bronx, and went on to become a literacy coach and earn her Masters of Science in Teaching. In her column she offers teaching and literacy tips for educators.

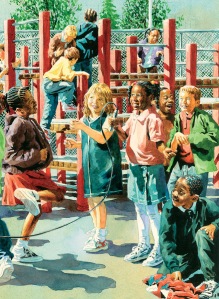

I live in Astoria, Queens, one of the most racially, culturally and ethnically diverse neighborhoods in New York, and my apartment building absolutely reflects that diversity. My neighbors are from Egypt, Bangladesh, and the Dominican Republic and the building is warm and lively, full of immigrant families with young children.

Last week, New York City public schools were closed for Rosh Hashanah, and on Monday, my neighbors’ children played in our building’s courtyard late into the night. My windows were open, and as I sat reading I caught snippets of their conversations as they laughed and ran and screamed and played. But when I stopped and I listened closely, it occurred to me that I kept hearing the same word over and over: the “n-word.”

It was just falling out of their mouths, every other word, as if it were just a synonym for “friend” or “dude.” This saddened me for a couple reasons:

1) For most of the children in my building, English is a second language. I can think of thousands of other words that they should be absorbing and using instead.

2) I also got the sense that the children – being so young and many being first generation Americans, and none of them black – didn’t understand the social and historical implications of the word. They may have known it was a “bad word,” but I would bet they didn’t understand why.

These were not hateful children. These were uninformed children. These were children parroting back a word they’d heard others use without understanding its power. These were children who needed to be taught about the weight of their words.

This got me thinking about the Common Core Standards. Seems like a bizarre leap, but it’s not, really; I’m a huge literacy nerd, and most of my thoughts can be traced back to curriculum.

On page 7 of the introduction, the authors of the Common Core discuss the intentions of the standards, and express that one of the traits of college-/career-ready students is that they come to understand other perspectives and cultures:

Students appreciate that the twenty-first-century classroom and workplace are settings in which people from often widely divergent cultures and who represent diverse experiences and perspectives must learn and work together. Students actively seek to understand other perspectives and cultures through reading and listening, and they are able to communicate effectively with people of varied backgrounds. They evaluate other points of view critically and constructively. Through reading great classic and contemporary works of literature representative of a variety of periods, cultures, and worldviews, students can vicariously inhabit worlds and have experiences much different than their own.

This is huge! In essence, it empowers educators to teach the big things, like tolerance, acceptance, and equality alongside math and science. In addition to teaching comprehension strategies, teachers more than ever can choose books to share with their students that take on some pretty powerful topics and use the literacy block to discuss, debate, respond, investigate and explain.

One of my favorite books on curriculum development and educational philosophy around teaching for social justice is Mary Cowhey’s Black Ants and Buddhists: Thinking Critically and Teaching Differently in the Primary Grades. Ms. Cowhey’s strength is her ability to navigate the delicate and difficult social issues and historical topics with young children, weaving it into the fabric of her literacy and social studies curriculum.

One of my favorite books on curriculum development and educational philosophy around teaching for social justice is Mary Cowhey’s Black Ants and Buddhists: Thinking Critically and Teaching Differently in the Primary Grades. Ms. Cowhey’s strength is her ability to navigate the delicate and difficult social issues and historical topics with young children, weaving it into the fabric of her literacy and social studies curriculum.

During one Read Aloud a week, Ms. Cowhey chooses a book that will provoke a philosophical discussion and uses the time to focus on listening and language standards, and peppered throughout the book are the titles of the texts she chooses (not surprisingly, some of the books she mentions are ours!). She includes a powerful chapter entitled “Nurturing History Detectives,” where she talks about how to get children to think critically about perspective when learning history, students that comprehend but can also critique. The Common Core Standards address this need, too:

“Students are engaged and open-minded—but discerning—readers and listeners. They work diligently to understand precisely what an author or speaker is saying, but they also question an author’s or speaker’s assumptions and premises and assess the veracity of claims and the soundness of reasoning.” (also page 7 of the Introduction)

If the idea of teaching tolerance excites you, and I hope it does, I urge you to check out her book. I think it will be an important resource as we make the shift to more rigorous, content/comprehension/critical thinking driven Common Core aligned curriculum.