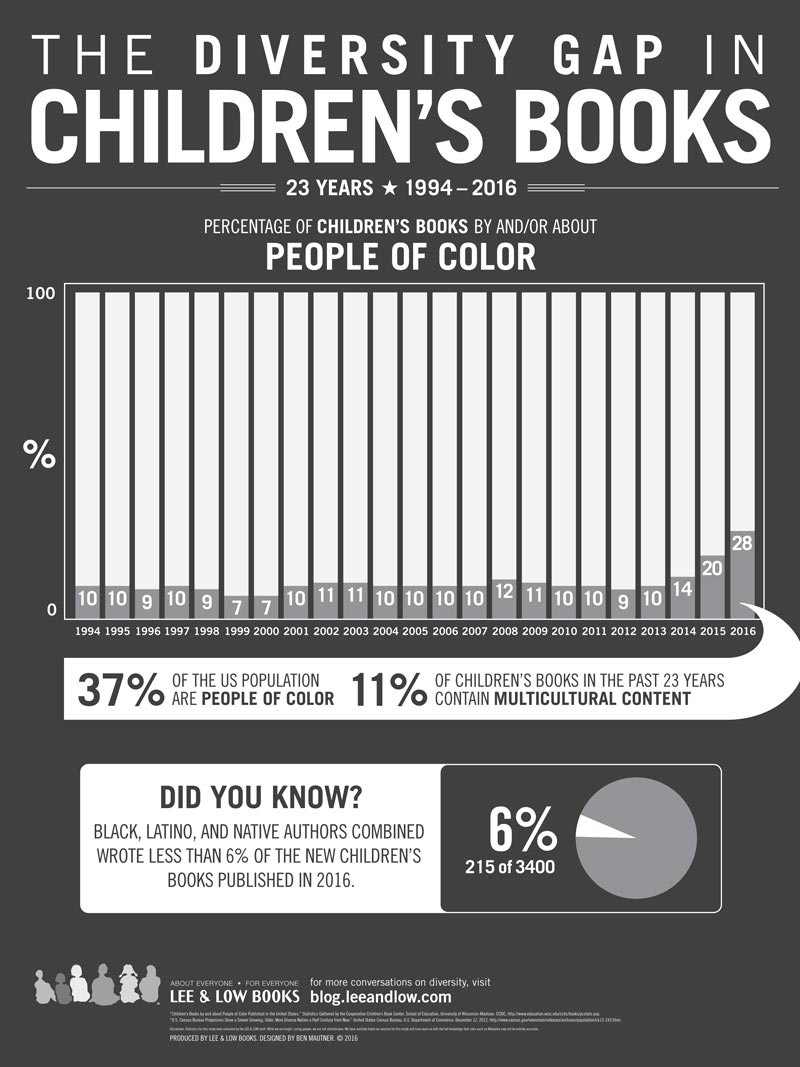

Last month, the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC) released its statistics on the number of children’s books by and about people of color published in 2016. Two years after the founding of We Need Diverse Books, the issue of diversity in children’s books continues to gain traction and media attention; it is the topic of panels, conferences, training sessions, and studies.

But is it all making a difference?

The answer is yes and no:

Holy heck, what an increase!

The number of diverse books being published each year stayed stagnant for more than two decades, but in 2014 it began increasing substantially. This year, the number jumped to 28% – the highest year on record since 1994 (and likely the highest year ever). 2016 also marked a number of important award wins for authors of color including a Caldecott Medal for Javaka Steptoe, a Caldecott Honor for Carole Boston Weatherford and R. Gregory Christie, a Newbery Honor for Ashley Bryan, and a Printz Award and Sibert Medal for Representative John Lewis.

But wait…

While the number of diverse books has increased substantially, the number of books written by people of color has not kept pace. In fact, in 2016, Black, Latinx, and Native authors combined wrote just 6% of new children’s books published. In other words, while the number of books with diverse content increases, the majority of those books are still written by white authors. We wrote about this phenomenon back in 2015, and the numbers haven’t changed much since then.

KT Horning delves into the data to look specifically at the consistent lack of representation for Black writers:

We can see that there are a whole lot of books being written about African Americans these days by people who are not African American. Does it matter? It certainly can. Especially when you care about authenticity.And, more significantly, this means we are not seeing African-American authors and artists being given the same opportunities to tell their own stories. In fact, last year just 71 of the 278 (25.5%) books about African-Americans were actually written and/or illustrated by African Americans.

Where do we go from here?

This year, the data includes some things to celebrate, and we should celebrate them! It’s amazing that in just a few years, the number of diverse books published has increased so substantially. Fighting for representation is hard and often thankless work, and it’s easy to become burnt out or pessimistic about the possibility of change. These numbers are a testament to those whose groundbreaking work has paved the way for more diversity and equity in publishing, people like Walter Dean Myers, Rudine Sims Bishop, and Debbie Reese. Change comes slowly, but the numbers tell us that it does indeed come.

At the same time, the numbers leave us with some questions that publishing as an industry must answer:

Why are we giving preference to white authors telling diverse stories rather than authors of color/Native authors?

Why are Black authors and illustrators still so underrepresented?

Since publishing is still largely white, what training are staff receiving to help them publish the increasing number of diverse stories with cultural awareness?

Until publishing answers these questions, the improving numbers will tell just part of the story.