Laleña Garcia has taught in New York City early childhood education programs for more than twenty years. What We Believe: A Black Lives Matter Principles Activity Book grew out of her work with Black Lives Matter in Schools, a teachers’ organization striving for racial equity in education. In this post, she shares more about how and why she developed this special project.

Talking About Big Ideas

Several of the teachers at the school where I teach five- and six-year-olds, Manhattan Country School, attended the Free Minds, Free People Conference in the summer of 2017, and came back to school with information about Black Lives Matter at School, and how it was becoming a national movement, so I attended one of the first organizing meetings of the New York City chapter in October, 2017. The first thing we did was a gallery walk, where all of the guiding principles were written out and taped on the walls. I didn’t even know there were guiding principles; like many people at that time, I understood BLM as a response to the murder of Trayvon Martin, but didn’t fully understand its breadth and scope as an affirmation of the society we should live in, rather than just a response to police violence, which, after all, is just one symptom of white supremacy and inequity in our society.

Several of the teachers at the school where I teach five- and six-year-olds, Manhattan Country School, attended the Free Minds, Free People Conference in the summer of 2017, and came back to school with information about Black Lives Matter at School, and how it was becoming a national movement, so I attended one of the first organizing meetings of the New York City chapter in October, 2017. The first thing we did was a gallery walk, where all of the guiding principles were written out and taped on the walls. I didn’t even know there were guiding principles; like many people at that time, I understood BLM as a response to the murder of Trayvon Martin, but didn’t fully understand its breadth and scope as an affirmation of the society we should live in, rather than just a response to police violence, which, after all, is just one symptom of white supremacy and inequity in our society.

I immediately knew that my contribution was going to be translating these amazing ideas into kid-friendly language so that early childhood and elementary teachers could have language to use; I love talking to little kids about big ideas. As an experienced early childhood educator (at that point, I’d been teaching for seventeen years), I knew that some educators would shy away from these conversations out of a (misguided) desire to protect young children from conversations about race (and other differences), but I also knew that many early childhood educators – who do have conversations about race, class, gender and family structures – would want to be involved because of their commitment to social justice, but would simultaneously be hesitant to bring up Black Lives Matter because of the horrific police violence the movement was responding to. As we split up into working groups, I joined the curriculum group, where my decision was bolstered by the need for early childhood curriculum: as one of the other organizers pointed out, there were lots of resources for middle and high school, and not so many for elementary school, while there were almost none for our youngest students.

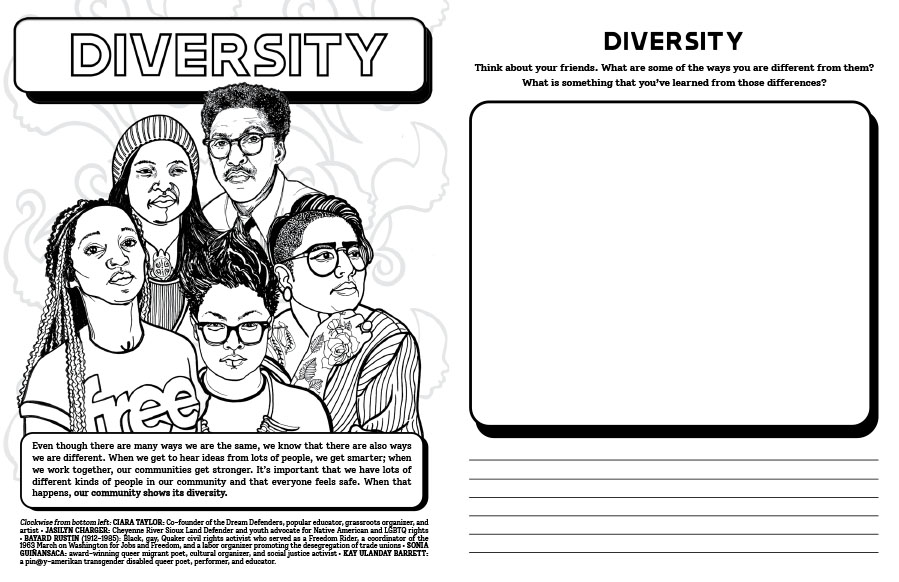

I offered to write language, as well as a short essay on how to bring up BLM by focusing on the principles, rather than the violence that sparked the movement, and set off to do so, giving myself a deadline of December, so that the language could be disseminated to teachers well in advance of the Week of Action in February. I thought about the developmental needs of young children, the ways in which many of the principles mirrored the environments created in early childhood classrooms, the support teachers might need in talking about a movement that some people saw as “controversial” or “political,” and got to work, using the definitions of each principle the national committee had provided. In the end, it took time, intense collaboration, and self-scrutiny, as I struggled with ways to remain true to the essence of each principle, while keeping the language simple and accessible. I talked to lots of early childhood educators, as well as trans educators and other queer educators to get feedback about the language to make sure it was not only age-appropriate but sensitive.

After I drafted language for each principle, and wrote a few paragraphs on how teachers could discuss the principles without focusing on the violence, I shared my work with the NYC and National Steering Committees; the national group made sure that this document was available to everyone who was using the curriculum resources, and I started hearing from teachers in Baltimore, Atlanta, and DC that the work I’d done was a valuable resource. I also workshopped the language in my school’s kindergarten classrooms, and our five- and six-year-olds were not only receptive but excited, and tried out the language themselves. Those original translations became the foundation for WHAT WE BELIEVE. The “letter to kids” at the end of the book was inspired by the conversation I had with our five- and six-year-olds after George Floyd was murdered last spring. One of the children asked, “But how did this all start?” Kids often ask that question, but, at this moment, in the midst of a pandemic, while I was so tired and teaching over Zoom, it felt even more overwhelming than usual. When I regained the ability to speak, I talked about stories, and systems, and the ways that kids always look confused when we talk about the ways the world is unfair because they don’t make sense; kids can’t understand the mental gymnastics adults have to do to convince ourselves that capitalism and white supremacy and patriarchy are logical, sensible reactions to the world. I truly believe that we need a world with systems and stories that make sense to a five-year-old, and deeply hope that they’re willing to help us out with creating those systems and stories. The principles of BLM are a great place to start, and if kids can begin their lives with the principles as a foundation, I believe they’ll have a much better shot at creating systems and stories for an equitable society.

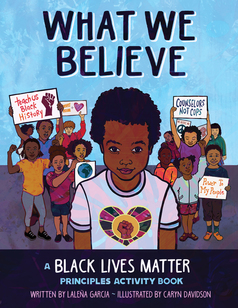

When illustrator Caryn Davidson shared the visual she’d created for the demands poster, I felt seen. I blurted out, “It’s me!” It wasn’t me, at all, but it was a Black girl, with glasses and purple hair. I’m a Black girl, with glasses and purple hair, and I never saw myself in books or pictures when I was a child. I spend a lot of time talking to my students (both kids and adults) about the importance of windows and mirrors in the books we read; often I introduce the book Raising Dragons, by Jerdine Nolan with a story about how happy I was, as an adult, when I first saw this book. “When I was a little girl,” I tell my kids, “I loved dragons, and I wanted to have adventures with dragons. But all the books about kids having adventures with dragons were about little white boys; there were no books with little brown girls and a dragon. So when I found this book, it made my heart happy.” I kind of felt that way when I saw the person Caryn had made for our posters. I want all my little brown kids to see themselves in the books they read, and given how seen I had felt when I saw Caryn’s work, I felt that other brown kids would also feel affirmed when they saw her work.

Laleña Garcia has taught in New York City early childhood education programs for more than twenty years. What We Believe grew out of her work with Black Lives Matter in Schools, a teachers’ organization striving for racial equity in education, and she has presented at local and national conferences on teaching the principles of the BLM movement to children. A graduate of Yale University and the Bank Street College of Education, she lives in Brooklyn, NY. Please visit her website at rootedkids.org and follow her on Instagram at @blm_in_kindergarten.

Laleña Garcia has taught in New York City early childhood education programs for more than twenty years. What We Believe grew out of her work with Black Lives Matter in Schools, a teachers’ organization striving for racial equity in education, and she has presented at local and national conferences on teaching the principles of the BLM movement to children. A graduate of Yale University and the Bank Street College of Education, she lives in Brooklyn, NY. Please visit her website at rootedkids.org and follow her on Instagram at @blm_in_kindergarten.