Last night, PBS announced the winner of their Great American Read, a poll to determine “America’s Favorite Novel.” The winner was To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, a story about racial tolerance that received 242,275 votes from a total of nearly 4.3 million cast.

According to PBS, the top 100 books were chosen by using the public opinion polling service “YouGov” to conduct “a demographically and statistically representative survey asking Americans to name their most-loved novel.” Once the Top 100 list was established, voting was opened to everyone to determine the winner and rankings of all 100 titles.

Given our focus on diversity and inclusion, we wondered how representative the list looked when compared to America’s demographics. Were authors of color represented? How did their books fare in the poll?

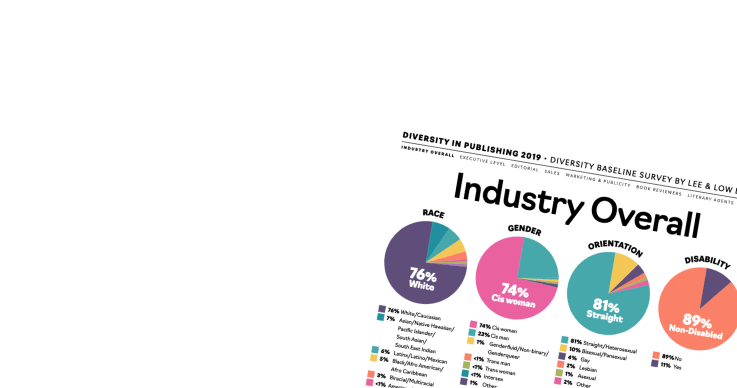

The results are a bit disheartening, if not surprising:

- One series by an author of color made it into the Top 10 (Outlander series)

- Three books by authors of color (Outlander series, The Joy Luck Club and The Color Purple) made it onto the Top 50

- Only 19 books by authors of color made it onto the Top 100

With poll-based lists like this one, it’s easy to swipe aside critiques about a lack of diversity by saying, “You can’t make people choose a book as their favorite!” But there are still some lessons I think we can take away from PBS’s experiment:

When it comes to the Western Canon, the deck is still stacked against diversity

Many of the books that made it highest in the polls would be considered “classics” of Western literature: books like To Kill a Mockingbird, Pride and Prejudice, Little Women, and Jane Eyre. Given that these books are key components of many curricula, the likelihood of them being read–and voted for–is much higher. Yet for many generations, the canon consisted almost entirely of books by and about white people. Diversifying the literature world, then, doesn’t just mean publishing more diverse books now. It also means working to get more classic diverse books–including some that may have been overlooked when they were first released–into the canon so that they can be read by more people and have the opportunity to become cultural touchstones.

Native voices remain absent

Not a single book on the Top 100 list of Great American Novels is by a Native author, which is a telling illustration of how Native voices in particular have been repeatedly erased from American history, art, and culture. Correcting this injustice requires an active effort on the part of all of us–parents, teachers, curriculum developers, librarians, booksellers, and readers–to read, recommend, and boost the profile of great stories that illuminate the Native perspective (in the children’s book world, one great place to start is the blog American Indians in Children’s Literature by Dr. Debbie Reese).

Diversity doesn’t just happen

One regular argument against the movement for more diverse books is that great books will naturally “rise” to the top, and that readers are “colorblind” and just want to read something good. But the makeup of this Top 100 list makes it pretty clear that, with no active effort to diversify reading, most people will still end up choosing books by and about white people, because those are the books that they were exposed to in school or that have been commercially successful enough to reach them en masse.

This is true for both individual readers and for those making reading decisions for others: curriculum developers, teachers, librarians, booksellers. Without making the decision to value diversity and be thoughtful about inclusion, many booklists will simply end up like the Top 100 list or NYC’s school reading list–mostly white, by default.

Only by choosing to actively build a diverse list of books will we end up with a truly American list of great books.