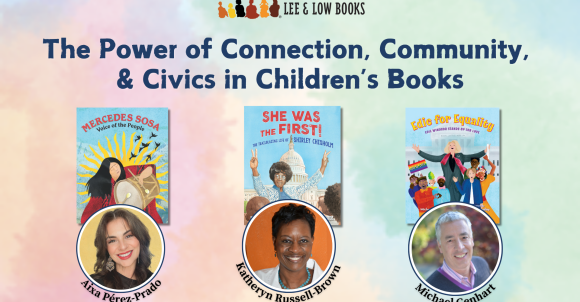

Thank you to all who joined us for our most recent webinar, The Power of Connection, Community & Civics in Children’s Books featuring authors Katheryn Russell-Brown (She Was the First!: The Trailblazing Life of Shirley Chisholm), Aixa Pérez-Prado (Mercedes Sosa: Voice of the People), and Michael Genhart (Edie For Equality: Edie Windsor Stands Up for Love).

If you missed it live (or just want to watch it again), you can access the webinar below, or here on YouTube. Click the links below for relevant resources and keep reading for an excerpt of the conversation.

Reach out for more information and/or a Professional Development certificate.

Below is an excerpt of the conversation. Click here for the full transcript.

Katie Potter:

We’ve talked a lot about their accomplishments and what they were known for, but now we’re going to dive in really to some strategies about about teaching. What advice do you have for educators about teaching these historical movements and figures? And how can we engage educators and families in these critical conversations?

Michael Genhart:

I’ll try to tackle those those questions the best I can. I want to start, though, with a shout out to educators, especially during these trying times. As a father of an elementary and middle school teacher, I hear from my daughter all the time how tough it’s it is. And the same for parents. They’re on the front line. Many, many, many fighting battles to not let others dictate what their child can read. So, I want to just put that out up front. I think we’re all in this together, hopefully.

But I have to say, I don’t really know what it’s actually like to be in the classroom, especially in in various states in the in the country. So, I’m going to offer a few thoughts, but it’s with complete humbleness that I share these ideas. Starting with it does feel like this is the time when we we need to get both louder and quieter at the same time. And I’ll explain what I mean by that.

The louder part to me is if we can keep these books in classroom libraries, in school libraries as resources for teachers and librarians and students and parents, please let’s do what we can to to make that happen because we know that succumbing to censorship is like agreeing with it, and that no resistance really matters. We also know that censorship and anti-DEI stuff and book banning is a real thing, of course, and that teachers are being mandated about what they can say and can’t say. And, in some cases, teachers can’t even talk about their own family, right?

We also know that words like “diversity” and “equity” and “inclusion” we cannot use in so many classrooms now. But, as I understand it, the language is changing. The educators are trying to change the language, so that these important conversations can continue, and that they’re not shut down. So, words like “belonging” and “building community” and “making room for for everyone,” these make sense to me, and I hope they they stick. But I also worry that even changing the language might be problematic in the future, especially with government agencies now being told, “Hey, if you learn of a colleague or a peer still doing the DEI stuff, that’s reportable.” So, are we entering a culture that involves reporting on your colleagues and peers? Obviously, that’s problematic. I think continuing to teach history is important. But I think it’s the values that [historical figures] embody that are maybe a lens through which the teaching can happen. By values I mean celebrating differences, and everyone wants equal protection and the same opportunities as everyone else.

So here comes the quieter part. I just wonder how many of these conversations that have been taking place in the classroom will need to be more at home with parents, and really engaging parents and supporting them. Many families have these conversations already, but in those that don’t, the importance of talking about people like Mercedes and Shirley and Edie, and all that they stand for, may have to happen around the kitchen table more and more where there aren’t those same restrictions.

And so, your question about Edie [Windsor] in the classroom in particular. I think talking about Edie is really more about talking about what she did and how she did it. That is, she was not a lesbian woman who was pushing a queer agenda. She was just fighting for fairness, what we all want. And so, I think, centering that, and centering the child. Remember, we’re talking about kids here, and that our goal really is to help develop good solid citizens, and good human beings. And so, we do that by hopefully teaching good good values, including things like respect. That’s all [Edie] wanted to be respected.

Katheryn Russell-Brown:

I think this is tied to the mentorship role that [Shirley Chisholm] played. She’s not just a historical figure, or like my kids like to say, “someone born in the 1900s like you, Mom.” But there is a clear connection. Her work, her efforts, her strategies are still relevant today. So, I think just in terms of her approach, that’s what I would say to that.

As far as not just being relevant, but just kind of how to get her story out there and stories like hers out there at a time when books that address race issues are being targeted, or books that talk about unpleasant but true histories are being targeted. And so, one of the things I thought about while Michael was talking was certainly, you know, kind of what the shift is, and has been in terms of being in the classroom versus being at home. But I think in terms of being able to expose more students to a broader group of stories, one way to do that might be to get stories from students presented in the classroom. And then that’s a way that they could be talked about. If students were, for instance, given an opportunity to interview a neighbor or to interview a friend of the family, and some of these stories come up, then teachers can talk about them in the context of what students have shared. So, I think this is going to require a level of creativity that may not have been asked before, but we can’t stop telling the stories. We can’t stop sharing them with children because it’s the truth. These stories represent real people, real fights, real political decisions. That’s just one thought I had is kind of turning things around and having children bringing them to the classroom where they can then be talked about because then teacher didn’t initiate it, or attempt to indoctrinate young people.

Aixa Pérez-Prado:

I’m going to answer this as a university professor, which is my other life besides children’s books, and also as an artist. I think that the focus should be on sort of inquiry over ideology. We’re really approaching these people, their histories, and their stories as a problem that we want to explore and discover with curiosity, like asking the questions, “Why did this happen? What if they’d done something else? What if their actions had been different? Why did the author make the choices to write about the person in this way? And why does the art look like that, as well?”

Most illustrators hide things all over their books, little Easter eggs. I have a bunch of hidden things in Mercedes book that I encourage children to question, like “Why is there a bird on every page, or is there a bird on every page? What does that represent?” So, really tapping into using these books as a vehicle to teach creative and critical thinking and inquiry-based pedagogy is where to go with this because it shifts the focus from we’re teaching history that not everyone wants us to teach to we’re teaching kids to think, and teaching kids to be curious, and teaching them to wonder, and teaching them to listen with understanding and empathy, and thinking flexibly and all of these habits of mind. I’m also a habits of mind trainer. So, I really focus on in my own teaching to inspire curiosity. And just as a musician will not play with one note, or an artist use only one color, or a show writer have only one character, we need a variety of colors, notes, tones, hues, and personalities in the classroom to bring up all kinds of questions and to really raise children’s curiosity about the world.

And I think all of these women that we’ve heard about are certainly figures that ask us to ask questions of them, and to be curious about how they made the choices they made in their lives. And every child is the main character of their own story, right? So, as Katheryn was talking about the storytelling or telling their own stories, I think that these books are also springboards for telling your own story, and inquiring about the own history of your family and the challenges that have come up, maybe as immigrants, or as for other reasons in your family. And how this could be a story. And how could you tell the story? Would you tell it in a book? Would you tell it in a painting? Would you tell it in music? How would you tell your own story? I think that’s really the way we have to tackle this new world we’re living in right now where books are being challenged for what they contain. Focusing it to books being used as vehicles of critical thinking, of discovery, and of inspiring curiosity and creativity in classrooms.