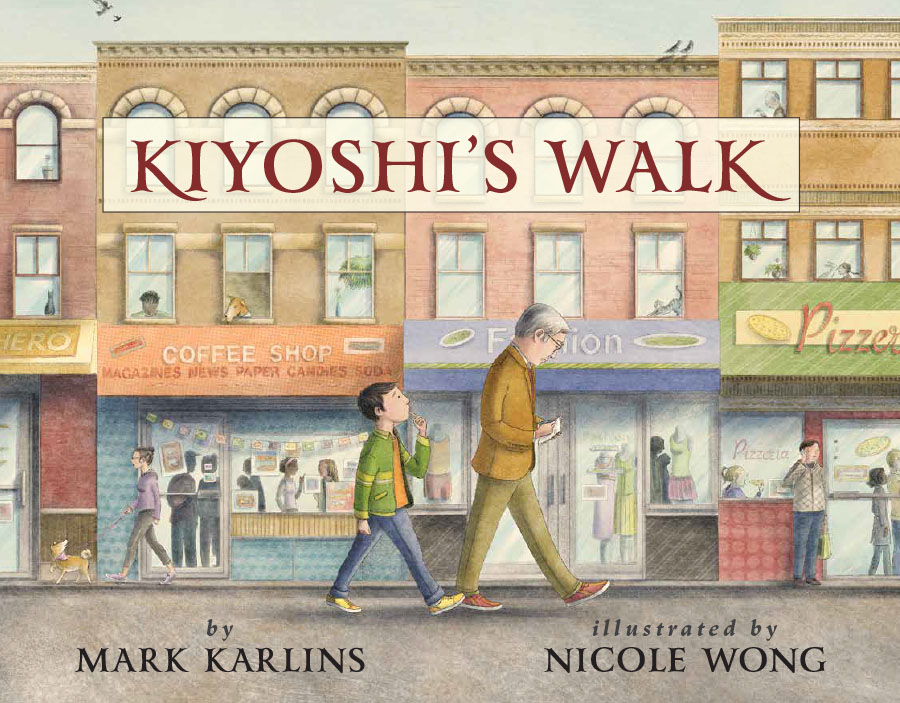

In this guest post, author and poet Mark Karlins shares how his latest title, Kiyoshi’s Walk, can be used to engage students (and anyone!) to write poetry in the classroom and at home. Mark Karlins also shares how the traditional Japanese poetry form, renga, can help create community in a classroom especially in time for National Poetry Month!

In this guest post, author and poet Mark Karlins shares how his latest title, Kiyoshi’s Walk, can be used to engage students (and anyone!) to write poetry in the classroom and at home. Mark Karlins also shares how the traditional Japanese poetry form, renga, can help create community in a classroom especially in time for National Poetry Month!

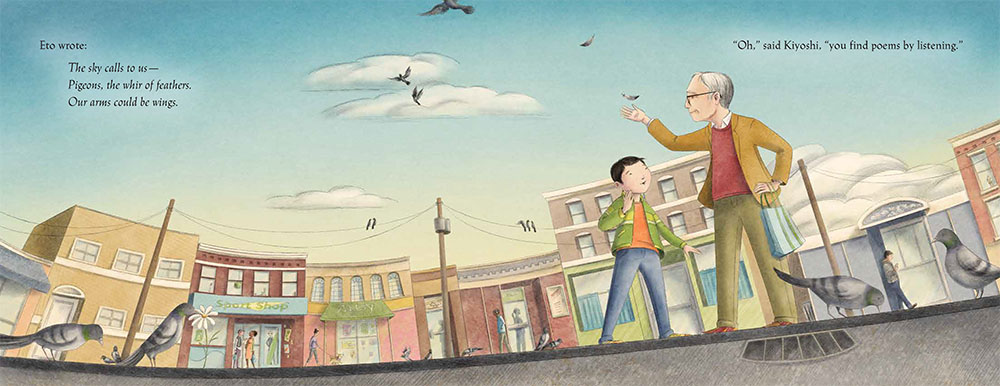

As I was writing Kiyoshi’s Walk, all I was thinking about was writing an engaging story about a child who wanted to learn to write poetry, a story which has a strong grandfather-grandchild relationship and a progressive structure that keeps people reading and listening. Now that Kiyoshi’s Walk has been published, I’ve begun to think about how the story can expand and become a base for teaching writing both at home and in the classroom. A walk outdoors with a parent and child, a stroll through the playground of a school, even an indoors excursion from one window to the next, can provide experiences for the writing of haiku. Grandfather Eto and Kiyoshi demonstrate a way this can happen.

But now I’d like to share with you another and rather different way to create poems as well. Renga, like haiku, is a traditional Japanese form of poetry. However renga are written by a group of poets as a collaborative effort. The first poet writes a three line haiku of 5-7-5 syllables. The second poet adds two lines, each of seven syllables. The third poet adds another haiku. The fourth adds another two lines, each of seven syllables, and so on. This structure repeats until the poem is finished, by the agreement of the poets.

Let’s use the following haiku from Kiyoshi’s Walk as an example:

The sky calls to us—

Pigeons, the whir of feathers.

Our arms could be wings.

If we take the haiku from above, about the pigeons, as a starting point and then follow that with responses, the resulting renga might become something like the following. (Please note that I have switched the writers from Eto and Kiyoshi to two poets—classmates, or friends, or teacher and student, or parent and child, etc.)

The sky calls to us— [5 syllables]

Pigeons, the whirr of feathers. [7}

Our arms could be wings. [5]

Second Poet:

We fly toward the stormy clouds [7]

And soon are swimming in rain. [7]

First Poet:

Inside the rain clouds [5]

A sudden glimmer of sun— [7]

I swim towards my friend. [5]

Second Poet:

Sidewalk flooded with warm rain. [7]

Our arms outstretched, feet splashing. [7]

In this example, just two poets are creating the renga. But the example I’ve presented has four stanzas and could just as easily have been created by four different poets. Six poets could create a six stanza renga, and even an entire class could write a renga together.

It is also possible to adapt the renga into a less formal linked poem. The basic rule for this collaborative project would be simple. One student writes a line of poetry and a new student writes the next line. This process continues with a new student creating the next line until the poem ends. A slightly different set up would be for 2 students (or 3, 4, 5. . .) to alternate in creating lines, i.e. 1, 2, 1,2, 1,2, etc. until the end.

To get students started it works best to give them a beginning line. For example, “I opened the door and walked into a forest,” or “As I walked down the street, a lion appeared.”

The instructions can be left as plain as that. I often find, though, that students do this assignment most comfortably if they are given an additional rule by the teacher, that each line must have a specified element. For example, a color, a sound, a body of water.

If you break the class into a number of groups, it is interesting to share the finished poems so that students can hear how each group developed the initial line. There are usually huge and surprising differences between the versions.

This process of creating poems in groups has an interesting result. The people involved become linked, through their minds and imaginations, into a community. In fact this was always one of the key aspects of renga, a group form created by writers in Japan for hundreds of years before the solo form of haiku evolved. Now renga or the linked form I’ve adapted from renga can help create community in a classroom or nearly any other group.

That is something I like to think about—that Kiyoshi’s Walk doesn’t end with its publication, that it can continue through children writing poems in their homes and schools and in other situations. Similar to Kiyoshi, they will find that poetry writing brings discovery and delight. As I’ve mentioned, the writing can be done either as the creative act of a single individual or as a group effort. Either way, the poems, if shared, will engender a sense of connection both to others and to the world. The playfulness and flexibility that are natural to the thought processes of children will not only be used, but developed into enduring skills.

Find more information about Kiyoshi’s Walk here.

Mark Karlins is the author of six picture books, two books of poetry for adults, and a number of reviews and essays on poetry. He runs poetry workshops for children and teenagers and has also taught at a number of colleges, including the MFA Program in Writing for Children and Young Adults at the Vermont College of Fine Arts. He lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico. You can find him on the Web at markkarlins.com.